Summary

If heretics go directly to hell, and saints go directly to heaven, what happens if you burn as a heretic someone who later turns out to be a saint? Em and Jesse talk about Dante, sainthood and the inquisitio process, and finally look at the cases of two female saints, one of whom was initially burned as a heretic, and one of whom was treated, ultimately, as a saint rather than a demoniac.

Annotations, Corrections, and Notes

1/ In fact, George Floyd was murdered on May 25th, so even though on the 31st it felt like the protests had been going on for weeks already, it was only one week, as noted, when we recorded this episode. Viva la revolution!

2/ Caroline Walker Bynum and Paul Freedman, Last Things: Death and the Apocalypse in the Middle Ages, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999 (link). [Quote from page 1.–Jesse]

3/ Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett, Good Omens. The miniseries (available on Prime) is extremely charming.

Jesse: For more on Margery Kempe, see episode 6, note 29; episode 7, note 23; and episode 8, note 4. For apophatic mysticism, see episode 7, notes 12 and 15 (and the whole section on Marguerite Porete.)

4/ Jesse: [The millennium] has to mark something. What does it mark?

Em: Bigger fines at Blockbuster video.

For our younger listeners, during the “Y2K Crisis,” people were worried that when the year turned to “2000,” computers would read it as “00” and assume it was 1900, thereby somehow messing up a bunch of things. This was solved by people updating computers to read a date stamp with a four-digit year instead of a two-digit one, and nothing happened, except in a few cases overdue videos were found to have absurd fees (which were then waived).

For our even younger listeners, Blockbuster Video was a place you could go to if you wanted to rent video cassettes and DVDs in the days before internet-based streaming services.

The last functioning Blockbuster Video is in Bend, OR.

5/ Back in the late 90s/early 2000s there was a series of movies about Americans fighting the end of the world: Independence Day, Armageddon, Deep Impact, The Day After Tomorrow, and The Core are just a few of the films in this genre. Will Smith does actually literally punch an alien in the face in Independence Day. [I love Will Smith, and I love this scene (relevant moment at 0:46.)–Jesse]

Jesse: Monster movies can signify many things, but Godzilla’s apocalyptic sensibility is a direct response to nuclear war, which had made the end of the world suddenly appear to be an achievable goal for humanity. Specifically, Godzilla is a response to the US dropping two atomic bombs on Japan and causing a humanitarian catastrophe in a manner not previously seen in global history. So while the movie contains the message that humanity has caused its own destruction (by awakening Godzilla), there’s also the stark reminder that only the US has ever dropped a nuclear bomb on a country, and that country was Japan.

6/ Supernova records: Supernova SN 185, which appeared in 185 CE, was the earliest supernova to make it into human records, although some researchers have suggested that HB9, which happened around 4600 BCE, may have been captured in rock carvings in Kashmir, India.

7/ Eschatology: The study of the end of the world. [Quote from Bynum and Freedman, page 3.–Jesse]

Jesse: For an example of Christ at the Last Judgment in a rainbow nimbus, see Giotto’s Last Judgment in the Scrovegni or Arena Chapel. The Doomsday pageant from the Middle English York Cycle play was produced by the Mercers, and a very famous document (the Mercers’ Indenture) from 1433 details all the items used in the pageant, including “A cloude & ij peces of rainbow of tymber” or “a cloud and two pieces of rainbow made of timber.” Presumably, the cloud and rainbow covered the “brandreth of Iren” (or iron) that Jesus sat on when he was lowered from and lifted back up to heaven at the beginning and end of the pageant. The document is reprinted in the Records of Early English Drama (or REED) York, volume 1, pages 55–56.

8/ The poem is “Harlem” by Langston Hughes. The play is A Raisin in the Sun, by Lorraine Hansberry.

Jesse: Lorraine Hansberry’s father case, Hansberry vs. Lee, deals specifically with restrictive covenants.

Harlem by Langston Hughes

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.Or does it explode?

Em: Redlining was a relatively common practice for quite a long time–technically, the term is used for any systematic denial of services to any group(s) of people. So if a bank were giving loans to White people with lower incomes but denying loans to Black people with the same or higher incomes, that is redlining. But so would be the police or fire department refusing to go to certain neighborhoods. The term originated from a time when banks drew on actual, paper maps to mark areas that were considered good and bad for investment–red lines meant risky area, do not invest here. In response, communities would create racial covenants in their housing deeds that would be used to keep non-White and Jewish people out of certain areas, thus creating the ethnicly/racially segregated neighborhoods we often associate with big cities without any need for the city’s government to do anything. In some places (like in nearby Monona, WI), there are some neighborhoods that still carry covenants within their paperwork stating to whom houses may or may not be sold–although they are unenforceable now, they can be extremely difficult to remove from deeds and such, so they remain as an unsavory reminder of our recent past. This article on racial covenants and redlining has a good overview. Covenants were declared illegal by the Supreme Court in 1948, but they persisted a while longer before falling into disuse. Redlining and other forms of housing discrimination have sadly persisted a lot longer.

Adam Ruins Everything video on redlining.

9/Jesse: Dante’s Inferno, Canto 19–the Simoniacs! For more on simony see Wikipedia. When I say “good pope” or “bad pope,” I am voicing Dante’s opinion, not my own.

Italian unification was in 1861. Papal infallibility is established in 1869–70. Vatican City is established as a modern independent city state in 1929.

For more on all this, see below, notes 11 and 12.

10/ Odysseus (aka Ulysses) is in the eighth ring of the eighth circle, along with Diomedes, reserved for counselors of fraud–because of all his schemes used to win the Trojan War. Dante would have been referring to the version of the Trojan War recounted in The Aeneid, so of course he doesn’t see Odysseus as one of the good guys. [To be fair, Homer wrote around 750 BCE. Once we get to 5th century Athens–i.e., democratic Athens during the 400s BCE, the century of the Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides–Odysseus is no longer a hero. The classical Greek plays depict Odysseus as Dante depicts him, because a man who can scheme and convince anyone to do anything by verbally manipulating them is obviously a danger to a democracy.–Jesse] [Em: I am weirdly disappointed to know this. Odysseus forever.]

11/ We talked a little about the pope losing the papal states in the notes from episode 8 (note 10). It was around 1870. The era in which the pope was basically a prisoner in the Vatican is called the Savoyard era and it stretches from 1870–1929. See also the first two minutes of this video.

12/ Specifically, the doctrine of papal infallibility was proclaimed in 1870 (first Vatican council), and it states the pope cannot “err or teach error when he speaks on matters of faith and morals ex cathedra” (source). Meaning that if you ask him what the weather is going to be and he tells you he thinks it will rain and then it doesn’t rain, there’s not considered to be a contradiction. However, per that same NYT article, it seems as though if he doesn’t declare that he’s speaking infallibly, it doesn’t necessarily count as infallible–the doctrine doesn’t mean all teachings the pope gives are assumed to be infallible ex post facto.

13/ Pope Nicholas III apparently got the job of pope through family connections (some connections!) and was never a priest until that point (although he was a cardinal earlier? Catholicism is weird).

14/ The next evil pope, per Dante, was Boniface VIII. Nicholas also predicts another evil pope, Clement V.

15/ New question: Who would we ADD to Dante’s Hell? You can only choose one. Clearly Stephen Miller belongs in the 8th circle / 8th ring. (Okay I will save it for the “Em Is Angry about Politics” podcast.)

The modern circle of Hell that can replace the sodomites is people who call meetings for things that could have been an email. (Clearly this is a form of pride? But a specific one that deserves mention.)

16/ “Our grandfather was taught to baptize kids…” Our grandfather was a cardiologist, so if he was taught to do baptisms it must have been part of the standard medical curriculum, because I don’t think he spent too much time doing deliveries. [All doctors were theoretically supposed to be able to reassure a parent that their child had been baptized in the case of a stillbirth. I don’t know if he *really* knew what to say, and I imagine that once Vatican II took hold it was no longer an issue. He did have a wonderful story about safely delivering a healthy baby in a car–just outside the hospital, I think–as a med student. When he proudly recounted the tale to one of his fellow residents, the guy just wanted to know what kind of car it had been.–Jesse]

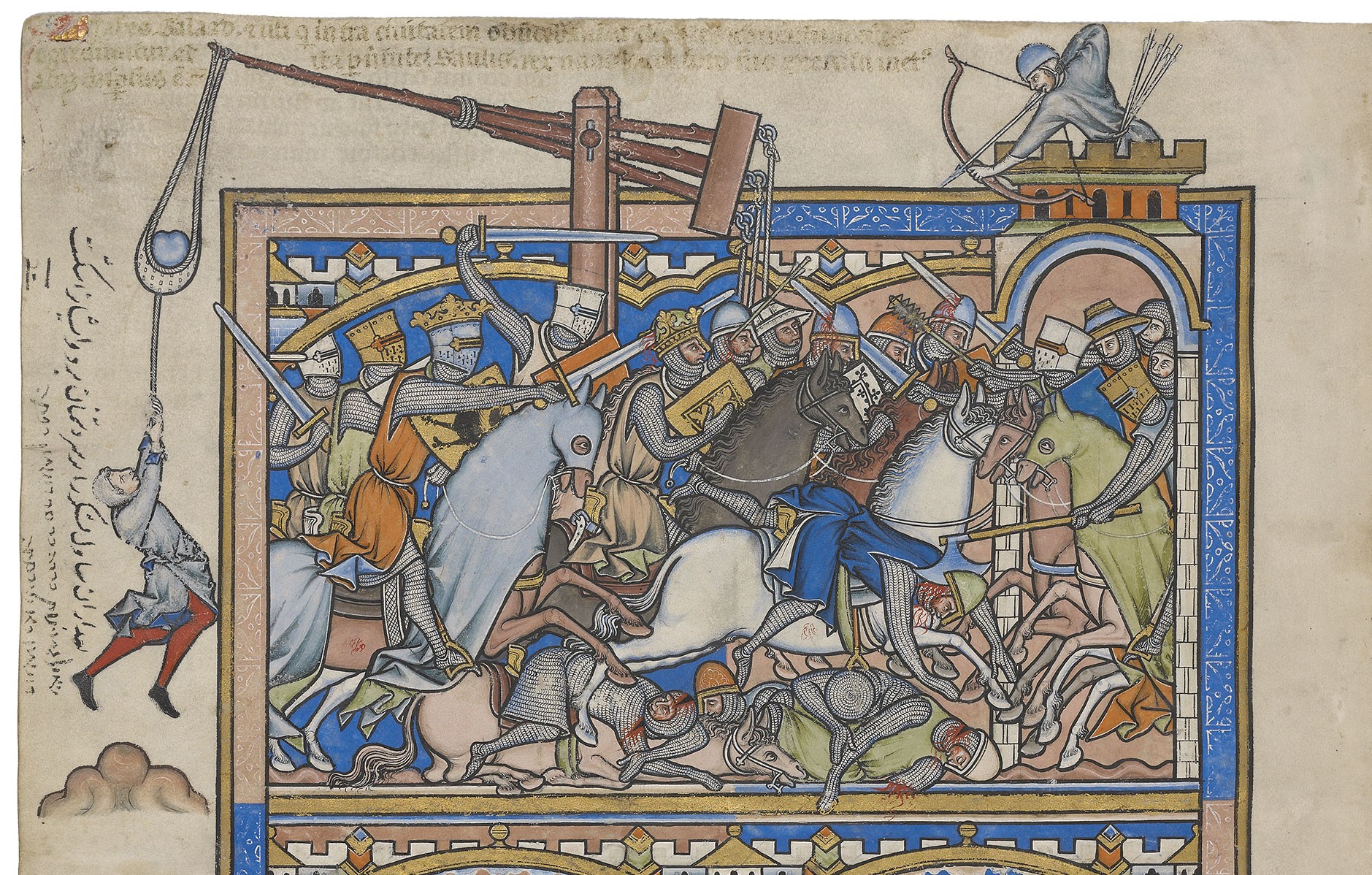

17/ Michael Camille, “The Pose of the Queer: Dante’s Gaze, Brunetto Latini’s Body,” in Queering the Middle Ages, Glenn Burger and Steven F. Kruger, eds. University of Minnesota Press, 2001. (Link). (PS If you buy and read this book, please leave it a nicer review than the current one that is up there on Amazon, which is crummy. Like dude, why did you do that.) This is the illustration:

As a side note, Brunetto Latini was a respected politician and philosopher who, among other things, was married (he had a daughter). A lot of the paper can be read here.

Jesse: Camille’s essay is great! Many gay and bisexual people throughout history have been married, of course, specifically to have children to carry on the family name and/or fortune, etc. Latini seems to have written at least one love poem to a man (one poem has been discovered so far), possibly to Bondie Dietaiuti. It’s important to note that Dante and Latini were friends, and they’re glad to see each other in this scene. It’s truly fascinating, because Dante draws a brilliant portrait of his former mentor Latini. Dante clearly admires and respects him, using the formal you/voi form that Dante presumably used in real life when Latini was alive. The scene is extremely moving, and it’s tempting to think that Dante treats Latini this way because homosexuality is a love-based sin. Presumably this is not how Dante viewed it when he wrote the Inferno, since he makes homosexuality a Seventh Circle-level sin (a sin of violence). Interestingly, Dante may have changed his mind about homosexuality by the time he wrote Purgatory, where homosexuality is a sin of incontinence (lust), the same as heterosexual sinners who sinned because of lust. So–maybe what we see here is Dante’s indecision on the sin of homosexuality. At any rate, Latini certainly isn’t ashamed (even though he’s in the Seventh Circle, which is fairly far in), and he and Dante have a wonderful conversation.

18/ Agnes Nutter explodes in episode 2 of the Good Omens miniseries.

19/ Kevin Smith, dir., Dogma. [Morgan Freeman has frequently played God, but that doesn’t manifest in possession, just in an awesome portrayal of God.–Jesse]

20/ Feast of Corpus Christi: See episode 6, notes 14 and 16 (and accompanying audio, of course).

21/ Jesse: For more on Dyan Eliot, Proving Woman, see episode 6, note 11. This comparison on testing people like gold is from page 282 (and check out Fallen Bodies as well). Latin probare (to prove). A probatio is a proof (the test itself or the evidence).

22/ [35:40] “The way you test people… is compared to the same test…that you gave a gold coin to prove that it is real.” For a minute I legit thought Jesse was going to say you bite the person making the claim (you bite a gold coin to look for teeth marks, which indicate gold + lead, a softer metal, and therefore a forged coin). But this is a slightly different type of test. (I know that there was at least one neurologist who wrote about it, and I think it was Harold Klawans in Toscanini’s Fumble, but it has been so long since I read it that I am not altogether sure.)

Jesse: Ha! Biting might work too. (Does she feel it? If not, the possession might be divine.)

23/ Jean Gerson: See episode 6, notes 25, 27, and 33 and also episode 8 (he’s mentioned in the audio accompanying note 9) because he keeps coming up for some reason.

Jesse: To find these Gerson’s “On distinguishing true from false revelations” (1401) in English translation, see McGuire’s Paulist press collection Jean Gerson: Early Works. Gerson compares testing the coin of spiritual revelation to testing gold on page 338. For more on Gerson’s texts mentioned here, see Elliott’s Proving Woman, 283–284. See Elliott’s introduction for this quote: “Ultimately, the distance between saint and heretic practically disappeared” (6).

An inquisitio is a seeking, searching, examining, inquiring.

24/ University of Paris, aka the Sorbonne: originally emerged in 1150 in association with the cathedral school of Notre Dame de Paris, it was officially chartered by King Philip II in 1200 and recognized by Pope Innocent III in 1215. It was the second oldest university in Europe (the University of Bologna being the oldest; although Oxford claims to be older) and, following a suppression during the French Revolution, was reestablished by Napoleon as the University of France in 1806 and remained open continuously until it was divided into thirteen autonomous universities in 1970. So…is it the same university today that opened in 1150? This is a Ship of Theseus question.

Jesse: a scholastic disputatio is an arguing, reasoning, or debate. As Dyan Elliott notes in Proving Woman, “[i]n the disputatio, a scholar first isolates an area of investigation in the form of a proposition, which is presented as a quaestio. The quaestio is then interrogated so that two opposing sides emerge,” one for the proposition and one against it (234, 236). The disputatio is also closely related to the inquisitio or inquisitional procedure. An inquisitio is an inquiry into heresy in which the inquisitor often “combines the roles of prosecutor and judge” (234).

Elliott comments that “the scholastic disputatio can be regarded as but another version of the inquisitio,” an academic variation in which “the verdict [is] preordained, the same side always wins” (234). This preordained ending is obviously dangerous, and helps explain why Gerson could not effectively defend Joan of Arc.

25/ Famously, Christopher Hitchens served as an advocat diaboli for Mother Theresa’s sainthood inquisition. Spoiler alert–she was still sainted. [Yes, but we don’t canonize people the way we used to, and it’s not just because of modern skepticism—a lot of it is based on medieval sKepticism (and sexism).–Jesse]

26/ Please at this juncture check out “The Inquisition,” from History of the World, Part I. Thank you (note, this is not 100% G rated, although you could probably show it on network TV). Additionally, nobody expects…the Spanish Inquisition.

27/ Joan of Arc (1412-May 30, 1431). Podcast recorded 589 years one day later. [Yay! She’s still awesome.–Jesse]

28/ Concerning the burning of witches.

Jesse: Quick language note–Henry IV was the first English king after the Norman Conquest to speak English as his first language. During the reign of Richard II (whom Henry IV deposed in 1399 and murdered in 1400), English had become an important literary language (see Chaucer, for example).

29/ Jesse: Christina the Astonishing or Mirabilis (1150-1224) from Sint Truiden (St Trond in French). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christina_the_Astonishing

Barbara Newman “Possessed by the Spirit: Devout Women, Demoniacs, and the Apostolic Life in the Thirteenth Century” Speculum Vol. 73, No. 3 (Jul., 1998), pp. 733–770.

WorldCat link to the translation of Thomas of Cantimpré’s Life of Christina the Astonishing.

Thomas of Cantimpré (1201–1272) was a Dominican who wrote a number of Lives of holy women.

30/ Richard Kieckhefer, another Northwestern scholar. Interestingly (for those of us who are devoted readers of fiction, anyway), there’s a fair amount about the Inquisition in The Name of the Rose without really discussing that the Inquisition was not the organized machine we usually think of (whose main weapons are fear, surprise, and an almost fanatical devotion to the pope–).

Jesse: See Kieckhefer’s “The Office of Inquisition and Medieval Heresy: The Transition from Personal to Institutional Jurisdiction,” in The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 46.1 (Jan 1995), pp. 36–61.

Conrad of Marburg (1180–1233)

Elizabeth of Hungary (1207–1231)

Pope Benedict XII (Jacques Fornier) (1285–1342)

31/ If I recall correctly, the records of the torture/questioning of the main character (Menocchio) in The Cheese and the Worms were quite detailed. But that’s a tale for another day.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download